with love to Jennifer, Kim, Janet, and Sam

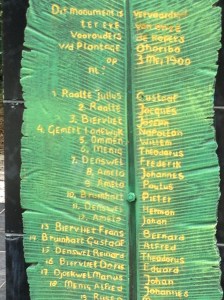

“A Subtlety or the Marvelous Sugar Baby an Homage to the unpaid and overworked Artisans who have refined our Sweet tastes from the cane fields to the Kitchens of the New World on the Occasion of the demolition of the Domino Sugar Refining Plant” is my third encounter with Kara Walker (also my fourth, fifth, and sixth). This time around, I a) knew who she was b) knew a little more about what to expect from her work, and c) was eager to see this homage to workers past and present. My mother is reading The Cost of Sugar and we are both, in our own way, processing our January visit to Suriname and our brief stop at Onoribo, the plantation we’re tied to. She wouldn’t use the word “process” and I probably shouldn’t either. That suggests something deliberate. I just know that its existence hovers over me with an inchoate sense of connection that I’m curious to see develop, perhaps into something more concrete. I really don’t know.

I had no idea I would visit “A Subtlety” so many times, and I didn’t know how protective I would end up feeling about it, particularly the sticky, haunting statues of children that greet visitors as they enter the factory and hang out in their own little spaces on the path to the Sphinx. I didn’t intend to write about the exhibit because I didn’t know how much it would spark echoes in me in pretty much all of the things I’m working on right now, mostly a lecture I’m preparing for Spring 2015, a chapter of my book on the history of the novel, and the course I’m teaching next semester on British Abolitionist literature. I didn’t expect it to remind me of “Belle” or “Saturday Night Live” or that it would confirm that I’ve been working out my third book project without knowing it. I thought I was just going to see what Walker was doing now, in a space a half-hour walk from my apartment in Bed-Stuy.

My first encounter with Walker’s work was at a keynote address at the annual meeting of the Society for the Study of Narrative. I can’t remember the year or even what paper I gave (I’m sure it had something pithy with “narrating” in the title and a colon and then some theory-heavy prose), and I only have a vague memory of being one of the only people of color in a room full of white academics discussing images that I found fascinating and provocative. I’d never even heard of her before that conference. It was before I’d visited the plantation worked by mother’s people and before I understood as fully as I do now the uniquely horribly way that white academics can treat their black peers. I was too taken by the images to pay attention to the argument. Because I encountered Walker in this white, heavily theorized space, I didn’t know that her work offended some black people. It hadn’t occurred to me that it would. This is, in part, because I grew up several times removed from the immediate impacts of American racism. My mother is from Suriname and a devoted citizen of Holland. She grew up knowing American racism was located in two places: Little Rock, Arkansas and Biloxi, Mississippi. She knew the lowest (slavery) and highest (Tubman, Parks, and King) moments in American history, but the structures of racism that weigh heavily on many African-Americans was not her burden, and I wasn’t raised to know that it was mine. My father is American but grew up in a pocket of New York populated by a rising black middle class (his childhood church was, and still is, on a block in Harlem called “Strivers’ Row”). As I got older, I heard stories of the bigotry he faced, but growing up as an Air-Force brat I lived in this odd cultural bubble that was, by design, integrated. I’m also on the lighter end of the color spectrum, and like all light-skinned (or, rather, light skinneded) people I have enjoyed an invisible privilege that has made it structurally easier for me to navigate predominately white spaces. What this has meant as an adult is that when I saw Walker’s images, I saw them as depictions of the past that happened to other black people and so engaged with them intellectually, primarily from a theoretical distance.

My second encounter with her work was in a completely different context. When I moved to Brooklyn, without realizing it or planning it, fell into a group of readers, writers, and artists. And so I ended up a guest of a guest at a dinner party out on Sag Harbor and the hosts were avid art collectors. Their summer home was so full of different pieces, in different rooms that it took me several hours to realize that I had been sitting next to and staring at a Kara Walker. It’s one of the few times I’ve experienced what Benjamin talks about as the aura of the original work in “Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” The truth of it was that I didn’t know I was in art collector’s home until I recognized the Walker piece and the effect of it—both the piece and her reputation—helped me see what I had mistaken for old posters and old chairs as a rather fascinating collection of art and art objects. Even still, I was more “oh how cool!” than reflective about the piece. I don’t know how I would have felt if the owners of the piece had been white (they’re African-American), and I still considered the work removed from the history it offers. It has taken me a few years to appreciate the juxtaposition of seeing a Walker piece, in an enclave of black privilege, while socially shucking corn and chatting with a woman who I later learned was a person of some consequence (I’ve since forgotten who she was). As exciting as it was to have been in this personal space with her work, it didn’t have much of an impact on me personally but was one of a string of accidental encounters I had with art and artists when I first moved to New York and bounced from cultural event to art opening as sport and leisure more than anything else.

This time with Walker was different.

I saw her work with Jennifer Williams. I wasn’t sure that I would get to see it with Jen (she’s a busy woman), but I knew I wanted to. She writes about Walker in a serious, sustained way, and I was lucky enough to hear her give a paper at the College Language Association conference earlier this year where she discussed Walker and Corregidora by Gayl Jones. The only time I’ve seen Walker in person I was with Jennifer. She’d taken me to an art event where people were eating caviar off of a naked woman and Walker showed up.

We wanted to see the exhibit as early as possible, so we walked from my apartment to a part of Williamsburg neither of us was very familiar with.

It was early May, and I’d just seen “Belle” and seen the Leslie Jones performance on “Saturday Night Live” that hurt me deep in my bones to watch. I hadn’t really connected the two, but by the time I left the Subtlety, they were linked to one another and my recent reading about Sarah Baartman brought them all together. I ended up seeing these three modern representations of black womanhood on a continuum that reduces brown female bodies and makes spectacles of us. The “us” here is important because whatever gap there has been between me and the images I first saw in Walker more than ten years ago has shrunk in ways I’m still figuring out. Here’s what I jotted down in my writing notebook after my first trip to the exhibit: In each of these moments—the small t.v. screen, the independent movie screen, and the almost cavernous space of the Domino Sugar Factory—a moment that honors and celebrates also forces us to confront the spectacle of exocticized black women’s bodies.

It was early May, and I’d just seen “Belle” and seen the Leslie Jones performance on “Saturday Night Live” that hurt me deep in my bones to watch. I hadn’t really connected the two, but by the time I left the Subtlety, they were linked to one another and my recent reading about Sarah Baartman brought them all together. I ended up seeing these three modern representations of black womanhood on a continuum that reduces brown female bodies and makes spectacles of us. The “us” here is important because whatever gap there has been between me and the images I first saw in Walker more than ten years ago has shrunk in ways I’m still figuring out. Here’s what I jotted down in my writing notebook after my first trip to the exhibit: In each of these moments—the small t.v. screen, the independent movie screen, and the almost cavernous space of the Domino Sugar Factory—a moment that honors and celebrates also forces us to confront the spectacle of exocticized black women’s bodies.

I was thinking of just how perfect and respectable Belle is in the movie. There’s a scene where she and her white cousin are both playing piano for a group of potential suitors. Her cousin’s performance is perfectly fine, but, even before she starts playing, you know Belle’s will be sublime and that it will prove to her detractors that she is not only just as good as they are but better. She has to be in order to prove her worth. And it still won’t be enough. She knows this and when she sits in her room alone, staring at herself in the mirror I see her coping with the same question Leslie Jones does in her “Saturday Night Live” debut about what it takes to be truly desired. It took me three or four times to get through that Leslie Jones sketch. I wasn’t as offended about the slavery rape joke as other people were. I could hear that it was offensive, but I didn’t feel offended by it; it’s possible that I couldn’t feel offended because I could only feel pained by the cost of admission Jones paid to write for “Saturday Night Live.” Tressie describes what Jones is doing as she tries to find a place for herself as desirable:

…she transitions into tropes about the value of big, tall, black female bodies like hers as valuable during slavery. By a different beauty measure, i.e. utility, Jones is saying she can hold her own against white beauty norms and the equally unattainable black exceptions that are made about once every popular culture generation (Lena Horne, Diana Ross, Diahann Carol, Pam Grier, Beyonce, Lupita, etc.). The punchline is that with her big bodied utility to white slave-owners she would have been guaranteed to have a man back in the olden days (emphasis mine).

…or, the horrific attentions of a white one. Dido Elizabeth Belle is a product of rape and no amount of nineteenth-century female accomplishment can erase that. The story goes that the historical Belle was the daughter of a navel officer and a slave. This is the same backstory that sets the events of the movie in motion. Her body is the path to inheritance for impoverished white men, but her skin is the obstacle that keeps her from being desirable. I don’t know if the screenwriter read A Woman of Colour; A Tale, originally published in 1808, but the story of a bi-racial woman, the daughter of a slave and her owner has a similar set of themes to those in the movie: marriage, inheritance, and nineteenth-century notions of ideal womanhood. In the novel, Olivia Fairfield (get it FAIRfield) negotiates the same terrain that “Belle” does in the movie and faces the same crude comments, questions, and exoticization. They are objects of fascination and disgust, and, to my mind, live on the same spectrum as Sarah Baartman. They bring the the spirit of the exhibit of Baartman, the so-called Hottentot Venus, into English parlors and courtship culture. Walker puts that culture right in your face.

I’m talking, of course, about the Sphinx’s vulva.

Roberta Smith’s review of the installation is the best one out there (even better than Hilton Als’), but it was important to me not to have anyone else in my head when I went to see it, so I didn’t read it until after I got home. It’s also why I went on the first day and Jennifer and I were among the first public group to see the exhibit. It’s why I didn’t know about the vulva. I should have known, of course. This is Walker we’re talking about after all, but Jennifer and I wandered around the factory taking it all in, slowly making our way towards the Sphinx. I was instantly enthralled and more interested in what I call the sugar babies, those little boys carrying baskets, with round brown cheeks similar to the ones I see on black folks everywhere. At the first one, I was very interested in the mini-lecture a white woman gave to explain what precisely “ a subtlety” was and how the desire for sugar contributed to slavery. Except she didn’t say “slavery” or “slaves” but used the word “servant” in its place. She lost me completely after that and I thought, “servant? bitch, please. ‘SLAVES’ is what they were!” I’m pretty sure that phrase appeared in a bubble above my head as I listened to her because folks started eyeing me warily.

I’d seen pictures of the Sphinx, though they could in no way capture the sheer size and aura of her, but the sugar babies were the most surprising thing to me.

Until I saw the vulva.

I was not part of that whole look-at-your-business-in-a-hand-mirror movement. Even when my dearest friend had the sex talk with me, the-real-unvarnished-sex talk, I never used the hand mirror she eventually mailed me. My favorite Angelou line might be, “I dance like I’ve got diamonds at the meeting of my thighs” and the truly fabulous poem mocking male poets for skipping over the “quim beneath a smock” in their poems praising female beauty used to be a staple in my “Man and Woman in Literature” class when I was a graduate student, but beyond making sure everything is working right, I was never much interested in pulling a Charlotte York and toppling over with a mirror in my hand.

Jennifer and I were shocked to see it, and my first thought was “oh, I get it! I can see what lesbians and straight men get so worked up about” and I thought it was beautiful. And then I remembered the poem “Cywydd to the Quim” that asks:

Why the sudden, boyish qualm

When it comes to praise the quim:

Beneath a smock, hairy splice

Split with a delicious slit?

People want to compare the Sphinx with Baartman (see here, here, here, here, and here). I can understand why; in fact, the working title of this blog post was “Hottentots and Sugar” (I realized the minute I walked past the gate that I would write about the exhibition at some point). Calling forth the spectre of the Hottentot Venus is the shorthand we often use when we see certain black female bodies on display, but I wonder how much of this is our unease with seeing those bodies outside of “respectable” spaces. The thing about the horrific exhibition of Baartman was that she was depicted as grotesque because her body type was different, viewed without her consent, prodded, dissected, and caricatured. Her bottom is depicted as disproportionate to the rest of her and her labia was reported and depicted as long and loose (called the “Hottentot Apron”) and those things are considered abnormal. The Sphinx evokes this but the difference are important. Yes she is prone and exposed but so large as to be invulnerable and impenetrable. She can be seen and photographed but not touched at all. The sheer size of her gives her agency Baartman could never have and far from grotesque I saw her oversized everything as beautiful, dignified, majestic. Seeing all of her toes so perfectly rendered and perfectly proportioned humanized her for me. They also made me giggle. There is something endearing about them.

I went back three more times after that. Jennifer went back too and we texted one another images of the changing exhibit.

My second visit was with Kim Hall, who is writing a book on women, race, labor, and the sugar trade. A lot of her work focuses on the seventeenth century, so my visit with her came with its own history lesson. The sugar babies (they are officially called “banana boys”) had started to decompose. In some instances they were falling apart. One little boy’s arm was broken and Kim explained how, when the slaves’ arms were caught in the machinery they would simply be cut off. The second time, because I knew the vulva was there, I wanted to see Kim’s reaction to it. Her eyes widened and then we were too distracted by the pictures people were taking to be much more than appalled and annoyed. Unable to touch the Sphynx, folks contented themselves with miming sexual acts. Kim noted the footprints in the sugar marking how close people tried to get to her.

My second visit was with Kim Hall, who is writing a book on women, race, labor, and the sugar trade. A lot of her work focuses on the seventeenth century, so my visit with her came with its own history lesson. The sugar babies (they are officially called “banana boys”) had started to decompose. In some instances they were falling apart. One little boy’s arm was broken and Kim explained how, when the slaves’ arms were caught in the machinery they would simply be cut off. The second time, because I knew the vulva was there, I wanted to see Kim’s reaction to it. Her eyes widened and then we were too distracted by the pictures people were taking to be much more than appalled and annoyed. Unable to touch the Sphynx, folks contented themselves with miming sexual acts. Kim noted the footprints in the sugar marking how close people tried to get to her.

When I spotted an Asian-American woman wearing a Creative Time badge I asked her what kind of pictures she saw folks taking. I’m embarrassed to say I only approached her because I assumed we would have some common, racialized response to these interactions with the installation. It was presumptuous of me to assume anything about her politics and, when I approached her with that knowing-black-lady-expression she was visibly annoyed and was quick to tell me that a whole black family took a picture posed at the rear of the Sphinx. I was incredulous and she admitted that they may have just “focused on the lower part.” She then went on to show me some great pictures about the prototype for the Sphinx and talked about how the exhibition was changing over time. She explained that brown sugar was being sprinkled on the banana boys and how some of them never made it to the exhibit. Kim being Kim meant that even in a part of Brooklyn she’d never been to she ran into friends and colleagues and between taking pictures of her own talked about the process with other academic types their for reasons similar to ours.

A brief word on irritating white folks being irritating and irritating me and every irritated black person I know

I said to Jennifer as we stood appalled at the sight and sound of white people treating the exhibit like a Disney World attraction, “this is the same reason they feel like they can touch our hair.” Not all of the white people I saw at the exhibit seemed blissfully unaware of the history that formed those images. The more I went, the more I learned about the exhibit and would talk about it with friends as we walked around, and there were always white folks nearby carefully listening. They were outnumbered by white folks in Tom’s shoes posing in ways you can easily find on the internet, but there were white people there who wanted some information about the exhibit, and they were happy listen to whatever knowledge I had. The space was mercifully uncurated. In other words, there was no docent there to talk to anybody about any of it. There were volunteers to answer questions and to keep people from touching the statues (and to warn people “step carefully, that sugar on the ground is very hard”). The title on the side of the building tells you what the piece is about and a directive not to touch but to take all of the pictures and to post those pictures on the internet is all the guidance we’re given.

It was foolish of me to expect people NOT to pretend to pinch the Sphinxes nipples or to make crude gestures about an oversized statue’s bottom. But it distracted me and my friends from our experience with this work. I didn’t expect (or even want) somber silence, but, I don’t know…

My frustration is about the reaction to the exhibit, but it goes beyond that. I’m so tired of white people who don’t get it, tired of people wearing blackface on Halloween, Native customs on Thanksgiving, and appropriating language and movement from those who developed that language and movement as a way to survive.

Karl Steel, a medievalist I know via twitter gently offered a counternarrative to some pictures I posted on twitter to show how I’ve seen white people interact with the installation. He does not dismiss the idea that I’m offended but argues that people who behave like jackasses are proving at least one point that Walker is trying to make with her work. He writes:

Had they been more familiar with her work, they’d know that by pretending to pinch the sphinx’s nipples or to stick their tongues in her vagina, by pretending, in short, to assault this defenseless yet gigantic woman, they’re just behaving like the creeps and racists that rampage through Walker’s work. They complete Walker’s Sphinx, because without that assault, we don’t have the kind of art that Walker normally makes. edit – what I mean to say here, because I want to make this as clear as possible, is that Walker, by design, has ensured that many of the visitors would make themselves living examples of exactly the kind of pervasive racism that her work rightly excoriates.

It’s an interesting view I hadn’t thought of, though my friend Ben tweeted the same idea to me at some point. I didn’t think of it in part because my engagement with Walker is limited to a conference and a dinner party but also because I wanted to engage with the work with a certain kind of audience. We had a brief discussion about it on line made all the more interesting because it’s a tricky thing for a white man and a black woman to talk about a black woman’s feelings about a representation of black womanhood…on the internet…where everybody could see. It was the kind of dialogue I think I was hoping for. More specifically, I think I wanted to be in that space with a diverse group of people who could get the piece as I did, like going to a movie where everyone chuckles or sighs with you and then you argue afterwards about what it might all mean. And I’m frustrated because even though I should no better, I know that’s not going to happen, even here in Brooklyn—perhaps especially here in Brooklyn where people are so sure of their liberal bonafides that they rarely consider how they perpetuate racism. After all, the whole purpose for the exhibit pays homage to a lack of integration in this hip and happening borough.

I would have been happy if there had been more of the kind of people I saw the exhibit with my third and fourth visits.

My third time I went with my favorite colleague Janet and her fabulous, wonderful husband Sam. I’ve known Janet for ten years (she co-chaired the committee that hired me), and when I first joined the English department, she would take me on these rambles and show me some part of New York I needed to know about and that was also fun. Of all the colleagues I have, she is the one who comes closest to what I hoped it would be like to be a professor. We are not limited to maddening department politics; in fact, we have visits when all we’ve talked about is make-up and movies. I still remember her taking me to her brother’s office so I could see an arerial view of The Gates in Central Park. Her real-world politics are inspiring. I’ve often said that there are white folks I know who would be sad (so sad with their fee-fees) I had to sit at the back of the bus and there are white folks I know who would burn the bus down until I could sit up front. Janet and Sam fall in the latter category. I wanted to see the exhibition with them because they are smart, fun, and interesting, but it was also way to show them a part of Brooklyn they don’t know so well. It was also a kind of thank you for introducing me to the City.

Janet teaches film, but brought up Blake’s “Chimney Sweeper” poems as we talked about the banana boys. With her and Sam, I got to engage with the work differently than I did with Jennifer and Kim. Jennifer and I were so awed by it, and Kim and I were there on a busy Friday with so many people that it was difficult to concentrate in any real way (we went to a café after and each did a bit of writing before we had dinner). In between being appalled by irritating white folks being irritating, Janet and I talked about how the decomposing sugar looked like blood (her observation), we talked about how the light hit the statues. We talked about the heartbreak of seeing the banana boys crumbling. Sam is a photographer, so he took pictures with Janet’s phone until the battery went out and then when with my phone. One of them, maybe Janet, explained that this same kind of disregard for history and suffering was on display when people visited concentration camps (that image left me speechless for a moment). Sam noted a woman having her friend take a picture as she bent over pretending to lick one of the banana boys as if he were a lollipop. He also noted a little black boy staring up into the face of another banana boy. It never occurred to me to take pictures of folks behaving badly, but I’m glad that Sam did. I don’t just mean that I’m glad I have the pictures because someone took them, but I’m glad that Sam is the someone who did. I don’t know why yet.

He took a lot of wonderful pictures, but this is my favorite.

He took a lot of wonderful pictures, but this is my favorite.

While we were there two Latino men covered in tattoos strode in and one said loudly, “I wanna see the slit!” His friend looked around nervously. Perhaps because I was one of the only few black people there but, I suspect, because my disdain for this behavior was a palpable thing and he could feel my glare before he saw it. Oddly, enough however, I was the least offended by these two guys. At first I thought it was because they were men of color, but ultimately I think I was rather amused and pleased. The idea of two men standing for an hour or more in the hot sun to see a huge naked woman cracked me up. I imagined the conversation and the debate that must have happened while they waited to get in. 90 minutes in the middle of summer is a long time to wait to see a thing you can view in under a minute. You can see it on the internet, so why bother to wait in line to see it in real life? It made me wish I were a poet or a proper writer so I could pretend to get inside their heads. If I had been thinking more clearly, I would have found a way to talk to them, not to preach or scold but to have a conversation, a chat, about what they thought. I might have pulled up the whole poem that teases men for avoiding “the slit.” (I’ll only quote the beginning here):

Every boorish, dullard poet

Who knows how to drink and prate,

(I will never give them board

Knowing I am better bred),

Prattles on in plaintive praise

Of girls’ assets without pause,

All, by Christ, incompetent.

Day in, day out, incontinent

Crawlers out to cadge a girl

Praise her hair as if the Grail

Was tangled in it. Lower

Down they go, and now glower

Over her eyebrows: her frown

Is bliss. Thus to the breasts, round

Between the arms, fit to burst,

And her hands, folded and blest.

I hate that I didn’t get to talk with them.

My final visit was on the second-to-last-day of the exhibit. I went by myself. I hadn’t planned to go again, but I heard that Free University had organized to have writers and other artists in the space to offer a different engagement than the one that seemed to be dominating the exhibit. It was the longest I’ve had to wait to get in (almost an hour and a half), and I was less interested in the exhibit at this point and more about watching the people engage with it. The space that was empty when Jen and I were there the first day was crowded with people.

I was curious to see what would happen to the spaces with voices of color deliberately raised. Creative Time put space aside for the Free University and I stood and listened to Sofía Gallisá reading in Spanish part of Abelardo Díaz Alfaro’s 1947 story “Bagazo” I don’t speak Spanish, but hearing it there nudged me out of my myopia. When Tracie Morris started with what was listed as “original sound poetry,” I’ll confess I moved away. I don’t have a lot of patience for spoken word poetry, by which I mean have no patience for it. I was also more interested in what would be like to be at the exhibit with so many black people. The other times I’ve been there the crowd had been overwhelming me white with pockets of black people here and there. Saturday it seemed like at least half of the people there were black. Parents brought their children, daughters were there with their mothers, and lovers were there holding hands. I saw black kids and families posing in front of the figures, and it didn’t bother me. Although I should know better by now, I’m sure I was projecting my own black experience onto the families, but mostly I couldn’t really concentrate on how other people were seeing the exhibit. Morris’ voice was clear and strong and it carried through the space. When I ran into her later, at the back of the Sphinx, I thanked her and explained that even thought I couldn’t hear what she was saying precisely, I could hear her voice and people responding to her and it pushed out whatever offensive nonsense I’d heard and seen in my earlier visits. She had disrupted the irritating. I paid attention this time around to the smell of sugar. It had been growing stronger the more we got into summer, but this time I noticed specific spots where it was particularly strong, almost suffocatingly so. I tried to see why, looking for vents or spaces to explain the difference. I had to step carefully, the melting sugar babies made it dangerous to move around easily. In some instances, they had fallen in such a way and melted to such a degree that it was almost impossible to get close to them. That seemed fitting.

Part of me wishes I was important enough to go back one more time, when Walker is there to oversee the dismantling. I’ve grown attached to the space and its current occupants and I’d like to see them again. I suspect that seeing the installation taken down would just upset me and make me cry. I can see myself standing there in that sticky mess crying and making it all messier.

Part of me wishes I was important enough to go back one more time, when Walker is there to oversee the dismantling. I’ve grown attached to the space and its current occupants and I’d like to see them again. I suspect that seeing the installation taken down would just upset me and make me cry. I can see myself standing there in that sticky mess crying and making it all messier.

My mom told me the other day about reading The Cost of Sugar and recognizing the names in the book as places from her childhood. She’s affectionately amused at my curiosity about “our” plantation. I still have no idea what to do with information I wasn’t seeking in the first place. I know they grew sugar in Suriname, but I think our plantation might have been too small to grow it. Maybe they grew it in Commewijne a larger plantation where my cousin now lives. I really don’t know.